The Russia-Ukraine Conflict 101:

What college students should know and why they should know it

Katie Burns

February 23, 2022

On Monday, Russian President Vladimir Putin publicly recognized the independence of two Ukrainian separatist regions—the “Donetsk People’s Republic” (DPR) and the “Luhansk People’s Republic” (LPR)—in a televised speech to Russia.

Putin’s speech highlighted potential “aid agreements” between the Kremlin and the pro-Russia separatists, which occupy the eastern Donbas region of Ukraine. He also sent Russian troops to the region—a move that signals an invasion to most world powers. However, Putin stated that the presence of his forces on Ukrainian soil is solely for “peacekeeping.”

Putin’s announcement essentially violates the Minsk agreements set between Russia and Ukraine in 2014-2015, which were a series of international agreements aimed to effectively end the wars in eastern Ukraine.

These events are some of the latest developments in the two nations’ nearly three decades of conflict. The modern root of this long-standing conflict ultimately concerns the future of Ukraine.

In short, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky wants membership in NATO amidst pressures from the Kremlin to preserve Russian influence in Ukraine, predominantly through the separatist groups occupying the Donbas region.

The Minsk agreements were a step in the right direction in establishing diplomacy between Russia and Ukraine. They required Ukraine to grant special status to the separatist groups while also calling for a ceasefire and pullback of troops and weapons following Russia’s annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula and months of separatist insurgency.

However, this conflict’s escalation and the recent amassment of an estimated 150,000 Russian troops on Ukrainian borders have proven the Minsk agreements to be largely ineffective.

Those seeking to understand the detailed history behind the Russia-Ukraine conflict can view NPR’s timeline by clicking the link below:

https://www.npr.org/2022/02/12/1080205477/history-ukraine-russia

Eduardo Magalhães III, Professor of Political Science at Simpson, specializes in comparative politics and international relations. He said that though this conflict is long and complicated, U.S. citizens should have a baseline understanding of what’s happening between Russia and Ukraine.

“The central reason to pay attention to what’s happening in Ukraine is because we’re very intimately tied with Europe, in terms of political relationships, cultural relationships and obviously economic relationships,” Magalhães said. “Conflict and war in Ukraine will have very dramatic effects on Europe and, consequently, very dramatic consequences on the U.S.”

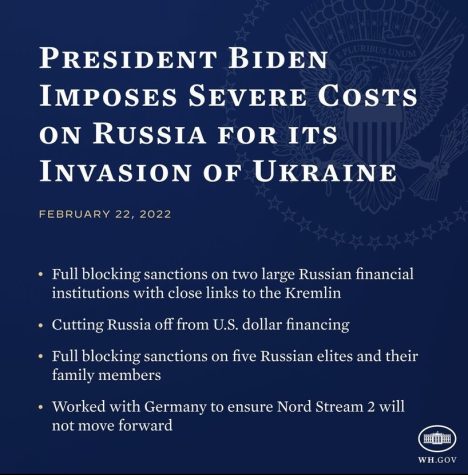

In the wake of Putin’s announcement, President Joe Biden announced his plan to impose severe sanctions on Russia on Tuesday. He briefly detailed this plan in the Instagram graphic below, with the caption: “Today, in close coordination with our Allies and partners, I am announcing the first tranche of sanctions to impose costs on Russia in response to yesterday’s actions.”

These sanctions are concerning to many, considering how Russia is one of the largest global oil and natural commodity exporters. Russian sanctions could (and likely will) translate to American pockets–inflation, gas, energy, and even shipping prices are expected to rise as Russian sanctions tighten. You can learn more about these economic implications here.

Magalhães thinks the U.S. and other European allies sanctioning Russia set an important precedent in the grand scheme of this conflict, despite the negative impacts it may have on the global economy.

“I definitely think it’s [sanctions] worth it in the sense that this cannot be allowed to stand, and it sets that precedent,” Magalhães said. “If the U.S. and the West did nothing or gave Russia a slap on the wrist, it may lead other authoritarian powers to do the same thing–so that’s part of the justification.”

Magalhães compares the economic implications of sanctions for Russia to that of someone’s savings account when put out of work.

“The other side of this justification is that we haven’t imposed these kinds of comprehensive sanctions on Russia before,” Magalhães said. “They may not instantly cripple the Russian economy, but it will certainly put them in a position where they’d have to burn through its foreign currency reserves.”

Senior Triniti Krauss will graduate with degrees in political science and global management; she feels that the responses from the U.S. and NATO thus far are more complicated.

“On one hand, U.S.-NATO action could provoke Russia and on the other hand, lack of action leaves Ukraine in a vulnerable place. In February, U.S. troops recently pulled out of Ukraine, leaving the country vulnerable. Then, yesterday, the U.S. and other NATO countries sanctioned Russia,” Krauss said. “Sanctions in the past have not been effective in achieving diplomatic goals, and the evacuation of U.S. troops obviously did not disincentivize Russia from engaging with Ukraine. I think so far that US-NATO actions have not been beneficial to Ukrainian civilians.”

When considering the positions and justifications between both nations, Magalhães believes Zelensky and the Ukrainian government are acting on behalf of their domestic interests as a sovereign nation.

“For Ukraine, they view long-term prospects of growth and development are tied to the West,” he said. “When you look at examples of former Eastern European countries that have joined the EU and NATO and how their people and economies have benefitted from that membership, so it makes perfect sense that the Ukrainian government and majority of the Ukrainian people see their future as being aligned with the West.”

When looking at the motivations behind Putin and the Kremlin, Magalhães feels it’s an issue of power dynamics coupled with the interests of the DPR and LPR.

“One catalyst is that these Ukrainian parties advocating for Russia have been experiencing substantial harassment and limits to their freedom in Ukrainian politics,” he said. “For Russia, it’s more of a great power dynamic. Part of this is this sort of ‘historical fear’ of the West that’s only mitigated by having a buffer. Geopolitically, Ukraine represents that buffer. So if Ukraine moves more firmly into the Western sphere, it creates a degree of insecurity for Putin.”

Magalhães notes that a degree of fault lies within the U.S. and NATO’s involvement in the conflict.

“There’s no question that the West has historically not demonstrated the level of commitment needed when responding to Russian threats and intervention,” he said. “I think there’s absolutely some fault to lay at the feet of the U.S.Germany, France, Great Britain and so on. When push came to shove, we’re like, ‘Well, we just don’t want to rock the boat,’ and that certainly doesn’t help Putin’s perception of our willingness to stand by behind these kinds of commitments.”

There’s been a level of WWIII-hysteria present within political discourse as Russia-Ukraine tensions continue to escalate. Fortunately, Magalhães feels that a full-fledged world war is unlikely to result from the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

“The likelihood of the West directly engaging with Russia on the battlefield is unlikely,” he said. “I think it’s much more irrational for Putin to do something that would provoke a direct military response […] Given the current situation, I think there would have to be a lot of unlikely dominoes that would have to fall before we would get into WWIII.”

Senior political science major Brady Leonard seconds this notion.

“The likelihood of an all-out war is always possible. Will it happen? At this moment in time, I don’t believe so,” Leonard said. “Yes, the U.S. has given warnings, but Russia has not directly attacked NATO or U.S. troops, so we aren’t really physically involved yet. I am concerned about other countries that the U.S. is not friendly with joining in [the conflict]. There is a whole lot that could come out of this, but only time will tell if it becomes a larger problem. An all-out war is and should be the last resort.”

Krauss’ studies in global management have caused her to become more well-versed in international relations topics than many Simpson students. Despite this, she said it’s essential that all students are aware of global affairs.

“We live in an incredibly interconnected world. Issues affecting other regions are likely affecting the U.S. directly or indirectly. It’s beneficial to familiarize ourselves in international affairs because it deepens our understanding of the lives and issues of other humans that we share the planet with,” she said. “The Russia-Ukraine situation will be a defining moment for NATO, an alliance that we’re part of. Whether you’re pro-NATO or against the alliance principally, understanding how our military alliances work in our world is incredibly important.”

Leonard echoes Krauss’ sentiments and believes the magnitude of the powers involved in the Russia-Ukraine conflict warrants attention from U.S. citizens and college students.

“We’ve already seen its effects on the world financially. If the U.S. does get involved, it will take from all of us,” Leonard said. “This could potentially be major world powers fighting each other, not the U.S. fighting people in a small country; it will involve a well-trained military following a rich and powerful leader. No matter what, it could damage everyone.”