Collaboration and sharing of notes has a fine line in academic dishonesty

February 11, 2013

On Friday, Feb. 1, one of the largest Ivy League scandals came to an end.

Michael Smith, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University announced that the scandal involving 125 Harvard students accused of cheating ended in forced withdrawals for over half the students.

The cheating scandal was exposed after a teaching assistant for the course Government 1310: “Introduction to Congress” found similarities in the take-home final exam. Assistant professor Matthew B. Platt presented the case to Harvard’s Administrative Board. Suspected students were placed under investigation for collusion on this exam after the Administrative Board thoroughly investigated all of the exams for Introduction to Congress. According to The New York Times, instructions for the exam stated students could not discuss the exam with others. The Harvard Crimson explained the format for the final exam.

“The final examination in “Introduction to Congress,” which included three multi-part short answer questions, a bonus short answer question and an essay question came with the instruction: “’The exam is completely open book, open note, open internet, etc. However, in all other regards, this should fall under similar guidelines that apply to in-class exams. More specifically, students may not discuss the exam with others—this includes resident tutors, writing centers, etc.’” Crimson staff writer Rebecca D. Robbins wrote.

However, many students found the instructions to be vague. Usual practices for exams involved sharing notes and reaching out to teaching fellows.

An article in The Crimson quoted a student who said she understood the easy possibility of collaboration because of the way the questions were formatted. She compared it to a take-home science exam.

Harvard’s cheating scandal has been detrimental to the institution’s reputation. Data from Harvard’s Administrative Board website shows an average of 17 students having to withdraw due to academic dishonesty. But more importantly, the cheating scandal has brought attention to the issue of academic dishonesty in higher education.

Here at Simpson College, academic dishonesty is not a light subject. Simpson trusts its students to show honesty and integrity in all situations, and a violation of that trust is never condoned. So far, there have already been 9 cases of academic dishonesty for this school year.

Simpson’s Academic Integrity Policy is posted on the college’s website. It explicitly shows what constitutes as academic dishonesty.

“Academic dishonesty includes (but is not limited to) any form of cheating, plagiarism, unauthorized collaboration, fraud (falsifying documents, forging signatures, altering records, etc.), misreporting any absence as college-sponsored or college-sanctioned, submitting a paper written in whole or in part by someone else, or submitting a paper that was previously submitted in whole or in substantial part for another class without prior permission,” the policy states. “If the student has any questions about whether any action would constitute academic dishonesty, it is imperative that he/she consult the instructor before taking the action.”

Steve Griffith, senior vice president and academic dean, has to handle every case of academic dishonesty.

Simpson has multiple categories when dealing with academic dishonesty consequences. Under policy, academic dishonesty that happens within the context of a certain course, with supporting evidence, results in the student failing the course, failing the assignment or redoing the assignment with a substituted assignment. The judgment and ultimate consequence is based on the professor’s discretion.

Academic dishonesty incidents outside the context of a course, such as transcript or document fraud, have different punishments. With substantial evidence, Dean Griffith then decides on what the student’s punishment will be, whether it is academic probation, academic suspension or academic dismissal. The entire case will then be placed in the student’s file for a permanent record.

A second offence of academic dishonesty results in Dean Griffith consulting the Academic Appeals Committee about necessary consequences.

However, sometimes substantial evidence may not be available in a suspected academic dishonesty incident. In those situations, professors issue a warning, report to Dean Griffith and decide on whether he or she needs to redo the assignment.

Students have the option to appeal any academic dishonesty accusations. He or she may schedule a meeting with the Academic Appeals Committee. The committee is the final decision maker in these cases.

Dean Griffith believes academic dishonesty is one of the worst things a student can do.

“To cheat on a test or a paper violates the trust, which results in severe repercussions,” Griffith said.

Similar situations to Harvard’s cheating scandal have occurred at Simpson but not to the same extent.

“There have been times when students did collaborate on projects,” Griffith said. “One person copied from another person, and there’s a line in there somewhere you can see.”

When the investigation into the Harvard cheating scandal started, the students said the accusations were merely a result of innocent collaboration among students and graduate-student teachers.

A senior told a New York Times reporter, “Everyone in this class had shared notes. You’d

expect similar answers.”

This is where the situation may be most controversial and confusing. In some instances, collaborating and discussing academic material with students encourages open discussion and learning. Sometimes, it’s simply not allowed because of academic integrity.

So where do college faculty draw the line?

Dean Griffith believes collaboration can be vague but firmly holds true to academic integrity.

“Sometimes collaboration has a shared language,” Griffith said.

He believes both professors and teachers need to be explicitly clear about certain cases when sharing notes and collaboration is inappropriate and accepted. There’s a fine line, and despite how accepted collaboration is, academic integrity needs to be the priority. He also said students sometimes commit academic dishonesty because of poor judgment.

“I think in my conversations with students, often, plagiarism cases occur when they get in a tight spot,” Griffith said. “People make a bad decision.”

Things like last minute, late night cramming and stringent deadlines sometimes cloud the judgment of some students, causing them to leave out citations or plagiarizing from the Internet.

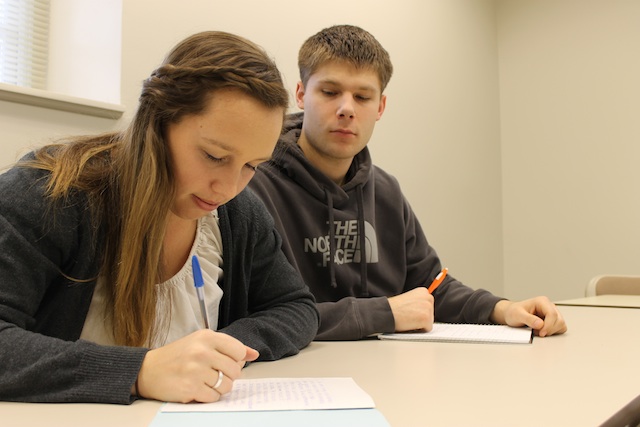

Two separate surveys were conducted to better understand where Simpson students and faculty stand on the issue of academic dishonesty.

For students who responded to the survey, 96 percent believe plagiarism is cheating, 61 percent think about cheating as a result of stress, 47 percent have cheated before on any type of academic assignment, 17 percent would not admit to cheating if questioned by authority and 33 percent do not know Simpson’s academic dishonesty policy.

Out of the 43 faculty members who responded to their respective survey, 86 percent have had to deal with academic dishonesty cases before, 86 percent try their hardest to make sure every student understands Simpson’s academic dishonesty policy, 6 percent have let academic dishonesty policies slide and 56 percent conduct take-home exams.

One question, however, raised some concerns for professors. It asked whether or not professors believed collaboration and sharing of notes constituted as academic dishonesty.

Four professors skipped the question because collaboration related to cheating is situational.

John Benoit, professor of music, was one of the four who skipped the question on the survey.

“For me, sharing of notes is fine because I know sometimes students miss a class,” Benoit said. “Also, when people take notes, myself included, you don’t always catch everything and sometimes your classmate might pick up what you missed, so I have no problems with students sharing their notes.”

Benoit does not require his students to maintain a graded notebook, but said he knows of some classes where students are required to maintain a graded notebook. In this instance, he believes sharing notes is a problem.

“For me, collaborating on homework is more of an issue, because that is something that the students are graded on individually,” Benoit said. “I always want to be confident that the work that I am receiving is the work that the students did.”

When students ask classmates questions because they are struggling with a certain part, Benoit sees no problem with that. But he is less comfortable when students work on homework or projects together. Benoit believes, often times, it is pretty clear the stronger student was the main contributor to the completion of the assignment.

Benoit feels Simpson has handled the topic of academic dishonesty in an organized fashion, primarily due to how it maintains a file for students who have been suspected of the problem before. This helps professors investigate into potential cheating problems.

What can be concluded from the Harvard cheating scandal and the response from Simpson’s community is how confusing collaboration and sharing of notes can be.

Students must adhere to academic policy, no matter the obstacles they face, Griffith said. Therefore, students need not cheat on homework assignments, individual projects, papers, lab reports or exams.

Griffith explained how Simpson has instilled a deep understanding of the severe consequences resulting from academic dishonesty. The Simpson Colloquium course, required for all incoming freshman, emphasizes how to properly cite sources in academic writing and teaches every detail about the academic dishonesty policy.

“I would say, just don’t cheat,” Griffith said. “Any outcome is better than that.”