Few Native land acknowledgements have been made by Iowa colleges

This article was written as a senior capstone project and was originally published to IowaWatch/Investigate Midwest on June 9, 2022

June 30, 2022

It saddens Queta Wanatee-Diego that some of her fellow University of Iowa students are unaware that Iowa was once inhabited by 17 Native American tribes.

“I have had people tell me that they didn’t even know that Native Americans were in Iowa or that Native Americans are still here and still thrive,” Wanatee-Diego, a U of I senior from the Meskwaki Settlement in Tama County, said.

One step colleges and universities in the U.S. are taking to raise awareness is through land acknowledgment statements.

Interviews with Native American students in Iowa, tribal members and state higher education officials over six months reveal the significance of such statements.

Some key findings:

- Tribal leaders and students say the statements are an empty gesture without further action. One Native student said they could be for PR. College leaders say it is important to go beyond statements.

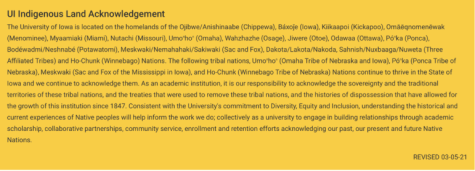

- All three of Iowa’s public universities — the University of Iowa, Iowa State University and the University of Northern Iowa — crafted land acknowledgement statements in the last three years, according to their institutional websites.

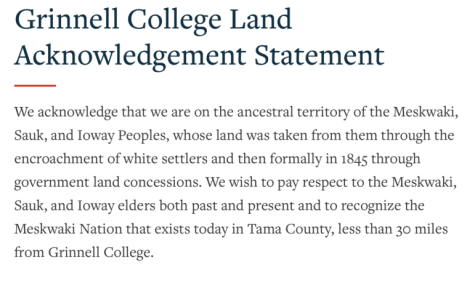

- Of the 23 private, four-year colleges and universities in Iowa, Drake University and Grinnell College are the two with an official institutional statement. Both published theirs within the last four years.

- Other schools say they are looking to develop them or have a statement in progress.

The statements matter to Native students such as Wanatee-Diego.

“I think it’s the first step, but it’s just scraping the surface of what schools need to do to bridge that achievement gap for Native American students,” she said.

Responding to the criticism from Iowa’s Native American community about the statements, state colleges said they were taking more concrete steps.

Simpson College is working with the Native American Inter-Tribal Student Alliance to educate and highlight accomplishments of Natives during November’s Native American Heritage Month activities and events, Keyah Levy, the college’s vice president of diversity, equity and inclusion, said.

The University of Northern Iowa spent two years in discussion with Meskwaki leaders on their statement.

“This was not done as a PR stunt, and we have not treated it as such. We’ve treated it as an opportunity to grow as a campus,” said Andrew Morse, chief of staff for UNI’s Office of Governmental Relations.

The University of Iowa’s Native American Council helped in creation of its university’s land acknowledgment statement.

“The acknowledgement is not a mandate, but rather is a resource and a way to recognize the rich history of our state,” said Liz Tovar, executive officer and associate vice president for the UI Division of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

More than 17,000 Native-identifying citizens live in the state today out of roughly 3.15 million residents, according to the State Library of Iowa. Roughly 1,450 derive from the Meskwaki Nation in central Iowa. The number of Native college students is more difficult to come to as some do not have a strong tie to their heritage or tribe.

Land acknowledgments aim to address past, present and future of a specific piece of land, namely how it relates to Native American and Indigenous communities, experts said.

Examining the Land Acknowledgment: Who do they serve?

Leah Slick-Driscoll, the history and Indigenous studies teacher at the Meskwaki Settlement School, has worked with several Iowa universities.

At a minimum, she said, the statement should share Native American displacement and the harsh impact of European colonization.

“It’s the beginning of acknowledging a genocidal past,” Slick-Driscoll said. “The fact of the matter is that 1% of the Native population was left within less than 300 years.

“If you really want to call yourself a democratic nation or an institution which serves the needs of people from various gender identities, racial backgrounds and priorities,” she continued, “you can’t just follow the status quo and keep on with a system of violence in which you don’t acknowledge.”

Terri Scott, director of higher education at the Meskwaki Settlement School, views land acknowledgements as a late apology.

“Others think that Native people are just a piece of history, almost giving a sense that we don’t belong today,” Scott said. “So, the preference is to keep us in a place where we’re not acknowledged fully. Historical land acknowledgements alone also keep us in that folder.”

Wanatee-Diego echoed some of these sentiments.

“I do think they’re needed to educate people. As I said, many don’t know Native American communities exist,” she said. “But, if you’re going to have a land acknowledgement, you do other things to back it up.”

People need to become more comfortable being uncomfortable with the harsh realities of how institutions got land, Wanatee-Diego said.

“Hearing those kinds of statements can be very eye-opening,” she said. “If nothing else, at least they’re aware of our side of the story, not just this black-and-white version of history.”

Smaller colleges likely face administrative barriers, former Simpson student Noah Trujillo said. Simpson is a four-year private college in Indianola, Iowa.

“It’s hard to say if there are problems with how the administration handles it when those needs may not be articulated, but maybe the administration should focus on finding those before they become a problem,” Trujillo said.

Trujillo, former co-president of Simpson’s Native American Inter-Tribal Student Alliance (NAISA), agrees land acknowledgements should contain real, raw language with genuine intentions.

“If you’re drafting something to educate an institution, that should be the first place you grapple with those uncomfortable truths,” Trujillo said. “I agree with the sentiment that colleges can also use them for PR.”

Simpson has yet to start a statement, but it is something Keyah Levy, Simpson’s vice president for diversity, equity and inclusion, said she would like to do.

‘A glimpse of the Native college experience’

Wanatee-Diego ended up at the University of Iowa after graduating from the Meskwaki school and first attending the University of Oregon her freshman year.

She knows she may be the only Native point of reference for her peers. She said she welcomes conversations and questions.

“I wanted to be that representation for my community and for my people in any way that I could,” she said.

Kaitlynne Reddy, who uses xe/xyr/xer pronouns, began college at Wartburg College in Waverly, Iowa, in 2018. Though Reddy now has a solid connection to the Oklahoma-Kickapoo heritage, Reddy identifies as a trans-racial adoptee, meaning xe was adopted at birth into a white family.

“There’s some disconnect between my culture and heritage compared to being raised by a white family, states away from where I was born — so I’ve always kind of been in the middle of things,” Reddy said.

However, Reddy has learned more about xyr ancestors and heritage in recent years.

“Everything that I have done regarding Indigenous people as a whole, or raising awareness, was done on my own accord,” Reddy said.

Wartburg leaders said they have started work on a land acknowledgement statement but put it on hold when the pandemic began and closed campus. “We did put the project on hold in hopes of returning to it when we would be able to better research who should be included in the acknowledgement and, just as importantly, how we could better support our Native American students through actions and not just words,” the college said in a statement.

Wartburg doesn’t have an official land acknowledgement but several professors and students use one. Reddy includes one in xyr email signature.

“It would be nice to see these other colleges and universities also have them. Once they’ve acknowledged traditional territories, what are they doing for those Native communities?” Reddy, who is taking a leave from academics, said. “Land acknowledgements must be paired with action.”

Institutions and other field experts weigh in

Dr. Sebastian Braun is the director of American Indian Studies at ISU. Braun said that before writing ISU’s land acknowledgment, some professors had their own statements in their syllabi or email signatures.

Braun felt a statement was vital in educating ISU students about Native people, especially after racial hate incidents on campus in fall 2019.

He also feels it’s crucial to communicate and form lasting relationships with Native communities.

“I think of land acknowledgement statements as incentives for further research and interest,” Braun said. “However, if you just have a statement, but you don’t engage with those communities, then it’s just a token.”

Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa, is in the process of writing its statement. Like ISU, its diversity committee is working with Meskwaki tribal members.

“We make statements all the time, but the next step — in terms of activism and restorative justice — is action,” said Hemie Collier, senior diversity officer at Cornell.

“We want to build a partnership with the nation moving forward,” Collier said. “If we at least understand that the land we’re on wasn’t initially Cornell’s, we then have a duty to make sure that we’re living up to the standards of what used to be here.”

Dr. Joyce Boss is Wartburg’s chair in world communities. She includes a land acknowledgement statement in her syllabi and has written additional statements for Wartburg students.

Boss moved to Iowa in the mid-90’s after growing up in California. She said discourse about Native communities in mainstream media centered around casinos in Iowa. After seeing the Native presence and culture in Iowa, Boss took it upon herself to learn more.

“I visited the Meskwaki Nation and Effigy Mounds National Monument several times,” Boss said. “It was amazing to learn about Native American history, not in generalities, but a very specific history of their relationship with land, natural resources and definitions of the sacred.”

The Effigy Mounds National Monument is located in Allamakee County, Iowa, and contains more than 200 preserved prehistoric mounds built by the indigenous Effigy Moundbuilders. The construction of mounds were primarily used for ceremonial burials, most formed into the shapes of birds, bear, deer, bison, lynx, turtle, panther, or water spirits.

Boss shared her land acknowledgement with others on campus but is unsure when or if they will officially adopt it.

In the meantime, Wartburg has a “land acknowledgment” tab on their social justice resources website page. The tab details what land acknowledgments are, how to make one and other general information. Boss said these resources were part of a larger diversity initiative for Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 2021.

The Native Americans in Iowa interviewed for this article believe institutional land acknowledgment statements are a productive step, but their main concern is action.

“Our culture and language mean everything to us,” Slick-Driscoll said. “We’re not going to waste time on people that are about something as frivolous as a piece of paper with a statement on it. That means nothing. If you want our time and young people to come to your university, we need to see action.”

This article was written as a senior capstone project and was originally published to IowaWatch/Investigate Midwest on June 9, 2022