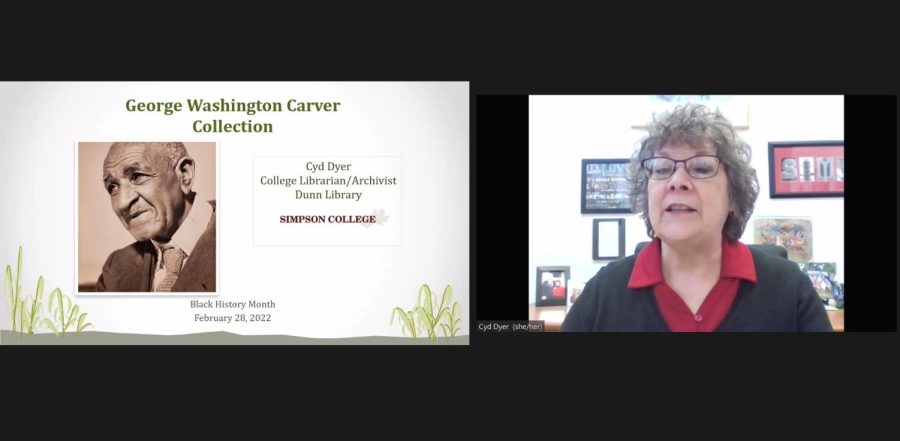

The George Washington Carver Collection with Cyd Dyer

Cyd Dyer presenting the George Washington Carver Collection.

March 2, 2022

Cyd Dyer, College Librarian and Archivist, gave a presentation on Dr. George Washington Carver via Zoom as the last of Simpson College’s Black History Month series on Feb. 28.

Dyer talked about George Washington Carver’s time at Simpson College and the unique connections between the two through stories and artifacts that are in the Carver Collection of the college archives.

“I’ve enjoyed pulling together these photographs, letters, interviews and stories to share with you,” Dyer said. “I focused on two questions: ‘What was the relationship between Carver and Simpson College?’ and ‘how is that relationship being honored today?’”

She began by giving a background of Dr. Carver, explaining that he was born into slavery on the farm of Diamond Grove, Mo., and, after the Civil War, was raised and educated by his former enslaver, Moses Carver, and Carver’s wife, Susan.

“George was often in frail health so he would work indoors, learning domestic skills,” Dyer said. “He then traveled through Missouri and Kansas to get further education. He did odd jobs to earn money, often setting up a laundry.”

In 1885, Carver sent an application to Highland University in Kansas and was accepted. However, when he arrived, he was told that he would not be admitted because he was Black.

Dyer says that Carver continued to work and then homesteaded in Kansas. Traveling north to Winterset, Iowa in 1888, he worked at the Schultz Hotel as a cook and started a laundry. While attending the Methodist Church, Carver became friends with Dr. John and Helen Milholland.

“Carver gave Mrs. Milholland painting lessons and they saw his artistic talent. The couple encouraged him to apply at Simpson,” Dyer said. “Carver learned from the college catalog that the new science hall at Simpson had an elegant art room immediately under the skylight.”

Also noted on the same page were other reasons for him to attend Simpson.

“There had not been for many years a saloon, hotel bar, nor billiard hall in the city. It is unusually quiet and pleasant and presents to the student as few unworthy attractions and allurements as any towns in the state,” Dyer said.

Dyer went on to explain the significance of Simpson College’s history. From the first three buildings (a ladies hall, the chapel, and the new science hall that had caught Carver’s eye) to the 350 students enrolled in preparatory business, art, music, teacher training and college courses.

“At age 26, Carver walked the 25 miles from Winterset to apply in person. On Sept. 9, he lined up at the chapel with others to register for classes,” Dyer said. “Both the registrar and President Edmund Holmes examined his high school records. Dr. Holmes reached out and shook Carver’s hand and said, ‘Welcome to Simpson.’”

Carver paid his $12 for the fall tuition as a select preparatory student and enrolled in grammar, arithmetic and writing courses. According to Joseph Walt, the college historian, Carver was probably the second Black student to attend Simpson.

“Carver’s real love was art, and he hoped he could enroll in the class taught by Miss Etta May Budd, Simpson’s art teacher,” Dyer said. “Miss Budd was unsure of his artistic abilities. After observing him for two weeks, she agreed to let him stay.”

Multiple of Carver’s artworks are in the college’s archive and some of them, as well as ones that feature him, still hang in Simpson’s halls today. Dyer showed some of these paintings as well as ones by Etta Budd and photos that feature both of them with the other members of the art class.

She also showed letters to and from Carver that noted his “humble, modest, and soft-spoken” nature.

“Despite his success in art, Miss Budd was concerned that his art would not earn enough for a living,” Dyer said. “She noticed his interest in nurturing plants, so perhaps he should study botany. Miss Budd persuaded Carver to transfer to an agricultural college, where her father, Dr. John Budd, was a professor of agriculture.

“Carver moved to Ames to attend the Iowa State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts. He was their first Black student,” Dyer said.

In 1894, Carver earned a Bachelor of Agriculture and was the college’s first Black graduate and Black faculty member, serving as an assistant botanist. He then went on to earn a Master of Science in agriculture.

And in 1928, Simpson was the first college to give Carver an honorary degree as Doctor of Science.

In an interview with President Gross, Carver said, “Oh, Simpson was the beginning. The friendly attitude of the people pushed me along. They made me believe I was a real human being.”

In a letter to Gross after the interview, Carver wrote, “It is impossible to tell you how much Simpson means to me. There is where I got my start of the inspiration to do what the great creator in his wisdom has empowered me to do.”

“Carver came by train from Tuskegee, to give Simpson’s graduating seniors their baccalaureate address on June 1,” Dyer said. “Carver’s talk was not written down or recorded. Over 2000 people attended, both inside and outside the Methodist church. He was scheduled to speak for 15 minutes. He talked about his relationship with his creator for more than an hour.”

Reporter Donald Grant wrote, “God said to take some peanuts apart and find out for yourself. Ye shall know science and science shall make you free. For science is the way of the truth.”

After his visit, Carver wrote, “I shudder to think what might have happened if Simpson College had closed its doors or failed to open them when I came, hungering and thirsting for an opportunity to develop as God gave me light and strength.”

On Jan. 5, 1943, Carver died. He was buried next to his mentor, Booker T. Washington. A resolution of respect was sent from Simpson to the Tuskegee Institute where he worked.

“The same year, Congress authorized the establishment of the George Washington Carver national monument at Carver’s birthplace in Missouri,” Dyer said. “It was the first federal monument and national park to be dedicated to an African American. Carver Hall was dedicated Oct. 6, 1956. Simpson was one of the first predominantly white colleges to name a building for an African American.”

Dyer ended the presentation by taking questions from her audience and thanking them for attending.