Shattering the glass ceiling of Iowa politics

March 27, 2018

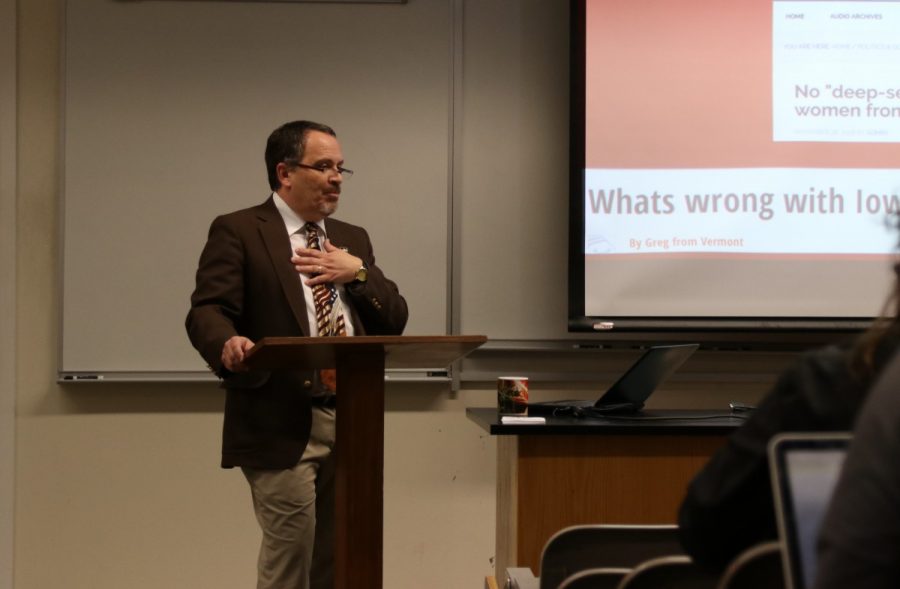

Curious to learn why it took Iowa until 2014 to first elect a woman to statewide office, Simpson professor of political science, Eduardo Magalhães III, spent a recent sabbatical digging into the history of women in Iowa politics.

He presented his findings to students and faculty on March 20 in a presentation titled “Unlucky in Death and Vacancies: Women and Political Milestones in Iowa.”

Magalhães found that, prior to Sen. Joni Ernst’s 2014 election, Iowa was the only state in the country besides Mississippi that hadn’t yet elected a woman to be either governor or member of the U.S. House or Senate.

“Overall, by 2008, these other 48 states had elected a total of 246 women to Congress and 24 women to the governor’s office,” Magalhães said.

To find out why that was, Magalhães first looked at the variables that his research indicated were strongly associated with the success of women candidates: having a population that is young, large, urban, educated and overall more diverse.

For his research, Magalhães analyzed demographic data from between 1962 and 2014, using 1990 as a midpoint.

In 1990, he found Iowa was the 37th most urbanized state, the 4th least diverse and the 44th youngest state by median age. Although Iowa ranked 12th in high school graduation, it was 37th in bachelor degree attainment and 43rd in advanced degree attainment.

Magalhães said when he began looking at the circumstances under which women candidates from other states won statewide office for the first time, a pattern began to emerge: Most of these women were widows of members of Congress who won special elections following the death of their husbands.

“From 1916 to 1964, 28 of 32 widows nominated for Congress won their seat, or an 88 percent winning rate,” he said. This contrasts with a 14 percent winning rate of women in the same time period who weren’t widows.

Magalhães said another major factor that determined the first-time success of women candidates who weren’t widows was whether or not they ran in an open election, as opposed to challenging an incumbent.

“You can ask any political scientist of any quality whatsoever, we have known forever that incumbents are very difficult to beat,” he said.

When he first began researching women in Iowa politics specifically, Magalhães said he assumed the incumbency advantage was the primary reason it took Iowa so long to elect a woman. This, along with the fact that Iowa politicians retire or die in office so rarely, proved to be the case.

He cited the fact that the incumbency advantage seems particularly strong in Iowa. For example, former Gov. Terry Branstad never lost an election to a challenger while in office. Also, in the last 25 years, there have been only two instances where a challenger beat an incumbent for statewide office.

When Sen. Ernst ran for the office she now occupies in 2014, it was in an open election after the previous office holder, Tom Harkin, retired. Meanwhile, Gov. Reynolds was appointed Iowa’s first woman governor after Branstad was appointed to be Ambassador to China.

Although it took Iowa a long time to finally elect women to office, Magalhães did highlight some of the state’s historical progressive milestones.

For example, in 1923, Emma J. Harvat from Iowa City was the first woman in the country to be elected mayor of a city with a population over 10,000. Iowa was also the 10th state to ratify the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote and the 4th state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment.

He also noted that between 1962 and 2014, Iowa saw more women run for statewide office, albeit unsuccessfully, than in other states with similar demographics.

“We may not have been perfect, but I don’t think you could argue that we had no respect or no acceptance of women candidates,” Magalhães said.

Commenting on this year’s midterm election, Magalhães said the governor’s race is interesting because Gov. Reynolds wasn’t technically elected to her position. However, he said he believes the incumbency advantage will likely still hold.