U.S. political advertising has a turbulent history

October 17, 2012

All it took was sixty-seconds, a little girl and a daisy flower; and the world of political advertising was forever changed.

Sept. 7, 1964 was the night the famous “Daisy Girl” ad aired for the democratic campaign during the presidential election.

The spot (short commercial) was a little girl plucking a daisy flower counting with each petal she pulled, followed by a narrator counting down to an explosion. Finishing with Lyndon Johnson’s slogan, “Vote for Johnson, the stakes are too high to stay home.”

Johnson ran the ad against republican candidate Barry Goldwater. The 50 million people that tuned in to watch were stunned.

Goldwater’s fans were outraged even though his name wasn’t mentioned in the ad once, according to Bob Mann, chair of Mass Communications Department at Louisiana State University.

The spot only aired one time, but that was all it took to make a difference.

“This Innocent little girl transformed the way that political advertising is done in America,” Mann said. “In a sixty-second spot that exploded, literally and figuratively, the way that American politicians sold themselves to the public.”

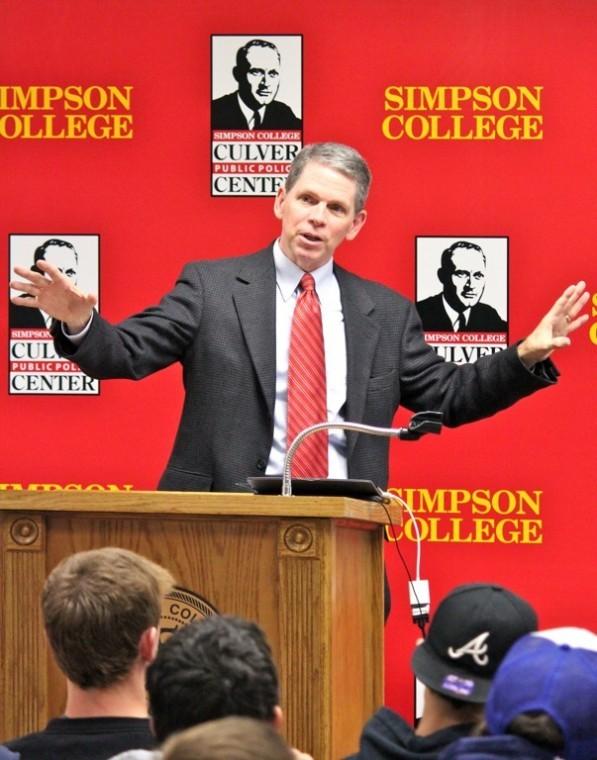

Mann is a journalist and politician historian who has published four books on top of working at Louisiana State University. Mann spoke at a forum event last week discussing the history and modern age of public advertising.

Prior to the 1964 election, political ads were simple and straightforward, which is why the “Daisy Girl” ad had such a big effect on campaigning.

A typical political advertisement in the 1950s’ and early 1960s’ consisted of people looking straight at the camera, delivering a message with no effort to engage the viewer, according to Mann.

“They contained very rational fact based appeals,” Mann said. “Most of the advertising done in the 1950s’ and 60’s by politics were not spot advertising, they were 30 minute speeches delivered looking into the camera.”

Even though they started to use spot ads more they still didn’t involve emotion or powerful messages at all, until Johnson ran the “Daisy Girl” ad.

When it dawned on political advertisers to play to the emotions of their audiences the change came very quickly, Mann said.

“It hit American politics like a bolt of lighting in the presidential election of 1964,” Mann said.

The company responsible for this change was the DDB (Doyle Dane Bernbach) Advertising Firm and Bill Bernbach, the creative genius of the firm.

At the time, DDB was in charge of advertising for Volkswagen Beetles, which weren’t being sold at a high rate.

Instead of opting for a traditional bland car advertisement, DDB came up with something completely new and fresh, causing sales of Volkswagen to increase.

“I don’t think anything represents the revolution that was going on in the late 50’s in advertising more vividly than automobile advertising,” Mann said.

These ads caught the eye of John F. Kennedy, who was president at the time. Kennedy decided he wanted DDB to do spots for him when he ran for reelection in 1964.

After Kennedy’s death, Johnson became the new democratic candidate and the democratic national committee continued to hire DDB for campaigning.

“That is probably the most momentous decision made in the history of political advertising because it changed the face of political advertising,” Mann said.

The first ad produced by them was the “Daisy Girl” spot. From there the creative ads against Goldwater continued to be aired, resulting in 27 total.

The 1964 election was a revolutionary campaign, bringing many firsts to idea of advertising.

“They showed a new generation of advertisers how to do it,” Mann said. “It was far more than just about giving information and who had the best facts. It was instead about which candidate could give meaning to the facts and fears that the voters already had.”

For senior Jordan Maher the fact that recent ads don’t contain any facts isn’t appealing.

“I don’t pay that much attention to them because there’s not much information, it’s just one candidate trying to make the other one look bad,” Maher said.

On top of using emotional appeals to connect to viewers, many advertisements started to rely on narrative and story to get a point across. These ideas are still seen in current political ads.

“I don’t think it’s an understatement to say that much of the political world that we experience today was born in the presidential campaign of 1964,”