Simpson announces counseling services changes while BSU demands go unmet

February 24, 2021

This story has since been updated. A new article will be posted on March 5.

On Feb. 17, Simpson College communications announced via email changes coming to health and counseling services starting in the 2021-2022 academic year.

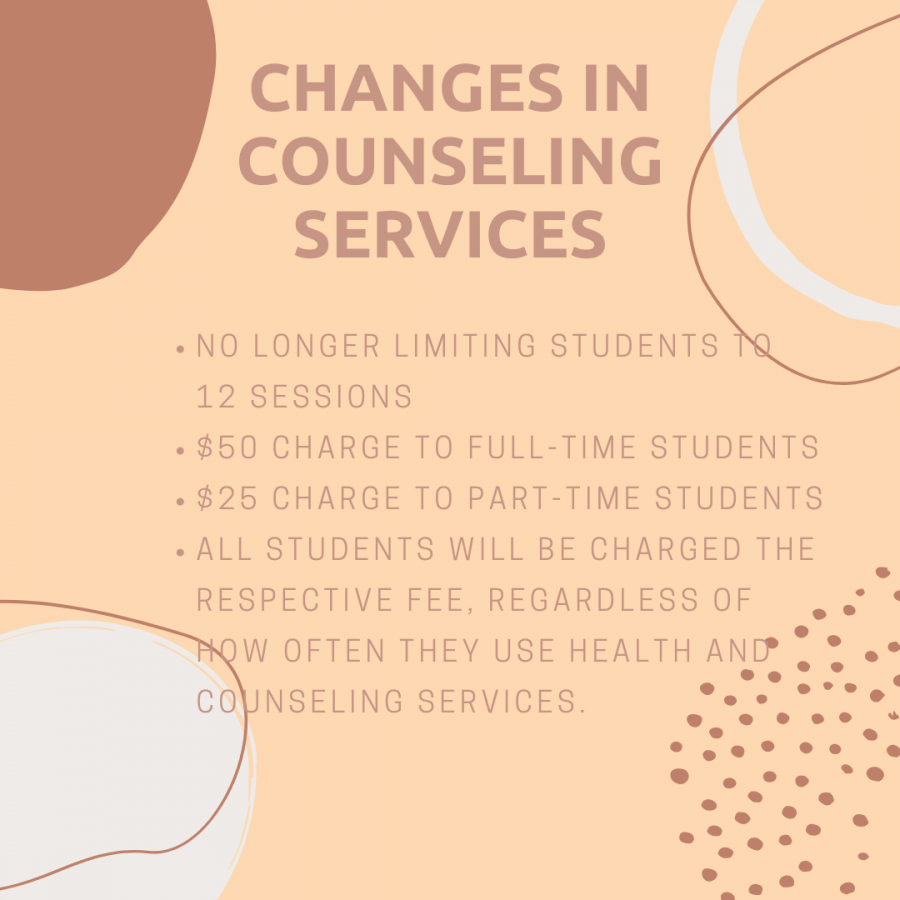

Changes coming to counseling services include no longer limiting students to 12 sessions per academic year and the addition of a full-time position. The position will be responsible for outreach and wellness programming, including training for students, faculty and staff about mental health support. New staff in health services–a nurse practitioner–will also be able to prescribe basic medication for depression and anxiety.

Changes will include increased staffing in health and counseling services and charging a wellness fee of $50 a semester for full-time students and $25 a semester for part-time students. All students will be charged the respective fee, regardless of how often they use health and counseling services.

“In the 2019-2020 academic year, Health and Counseling conducted a focus group of students to assess their satisfaction with our services,” the email read. “The additions covered by this new fee were identified by students as priorities among the student body. The demand for both health and mental health services continues to increase and has for some time. COVID has only increased this demand further.”

While the email cites student demand and the benefits of these incoming changes, one demand remains unmet: diversity in counseling services. In the wake of last semester’s Zoom bombing and the protest that followed, Simpson’s Black Student Union (BSU) had a list of demands to be met by the Simpson College administration. One such demand included providing at least one counselor who is a person of color.

Junior Tatum Clayburn said students came forward about the difficulty of speaking about experiences such as racial trauma with white counselors. The gap in lived experiences was too large, she said, hence calls for increased diversity among counseling staff. One counselor was promoted from part-time to a full time position, but the demand is specifically for a full-time counselor of color.

“You shouldn’t have to go into counseling and completely have to relive through your trauma, just for another person to be like, ‘You need to take time for yourself,’” Clayburn said. “What everyone was asking for was to get more mental health resources, specifically geared towards people of color and minorities on campus.”

In terms of the fees coming as part of the changes to counseling services, Clayburn said students should not have to pay a fee to ensure their own mental wellbeing, especially during a pandemic and when racist acts happen on campus.

“Adding a fee is just kind of shady, especially what happened this year,” Clayburn said. “I’m paying to get an education; I was hate-crimed at the institution at which I’m being educated. And now you’re going to make me pay to fix the mental trauma that you let happen.”

These issues have been raised before in the meetings with college officials that followed last semester’s protest. According to junior Pascasie Redhage, since then, she has neither spoken directly to President Kelliher and Heidi Levine nor received direct updates on progress. Kelliher, Redhage said, believes the demands made last semester, including increased diversity in counseling services, have been resolved.

“Counseling services can only do as much as the college is willing to fund them to do,” Redhage said. “At the moment, the only thing that college is willing to fund is a variation of a few things. [The college hasn’t] made any concrete decisions on how they’re funding this, yet; they just know that they have ‘x’ amount of dollars they can allocate in any direction they want.”

One direction included offering students of color on campus one free initial visit to a counselor in Des Moines, a Black woman. After that, students must fund future visits themselves or through their insurance. This offer is still standing.

“When they came to the BSU meeting,” Redhage said, “we discussed a variety of ways to not have that be the case. I know [associate dean for counseling, health, and leadership] Ellie Olson wants to get a partnership with a Black counselor within the next month. What that looks like has not been discussed with us as of right now.”

Redhage noted that a committee advocating for student interests, including interests related to counseling services, exists: the All-Campus Committee on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (ACCDEI). Redhage and Clayburn are both parts of this committee. The problem, she said, is ACCDEI’s attempts to communicate with the college have gone ignored.

“That committee has been the sole leadership on student demands,” Redhage said. “They’ve drafted up the entire policy, and they are doing the best they can to advocate for what the students want and what the faculty wants on [diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI)] initiatives. But the administration just continues to ignore them and us, which is frustrating because why create a committee if you aren’t going to listen?”