Expert: Faculty display microaggressions more than students

1/3 student population experiences some sort of MA

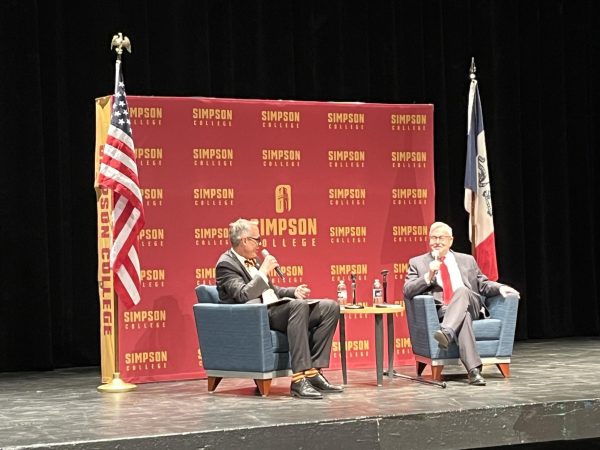

Tasha Souza, professor of communication and associate director of the Center for Teaching and Learning at Boise State University in Idaho, led an interactive workshop Wednesday in Hubbell Hall, diving into microaggressions and how to combat them. (Photo: Alex Kirkpatrick, Digital Editor/The Simpsonian)

January 26, 2017

INDIANOLA, Iowa — College faculty members are more likely than students to be instigators of microaggressions — which are subtle verbal communications, intentional or not, resulting in harmful consequences to members of marginalized groups — said one expert who spoke on Wednesday afternoon at Simpson College.

Tasha Souza, professor of communication and associated director of the Center for Teaching and Learning at Boise State University in Idaho, held an interactive workshop in Hubbell Hall with about 200 attendees, explaining that microaggressions are “often rooted in our conscious bias” and affect at least one-third of the student population.

The goal of the workshop was to help students, faculty and staff feel more empowered to respond with microresistance when confronted with a microaggression.

“We live in a society where there is systemic racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism, classism, ableism and American imperialism, and those are pervasive,” said Souza, who has been published in the areas of difficult dialogues in the classroom, transforming classroom conflict, discussion-based teaching, instructional communication and intercultural conflict. “And sadly, institutions of higher education are not immune.”

Through different scenarios, Souza had the audience re-enact situations in which one partner was the microaggressor and the other played the target.

The most common types of microaggressions include those that undermine the intelligence and competence of students, assuming a student is not from the United States, suggestion an important part of one’s identity or experience is unimportant and assuming one person can speak on behalf of an entire group.

The harm, Souza said, is that each microaggression is “a toxic raindrop that falls corrosively over time on its victim’s well-being and into learning environments.”

“As an instructor, your responsibility is to maintain a positive learning environment, an environment in which everyone can learn,” Souza said.

Jan Everhart, professor of religion at Simpson, has been teaching at the institution since 2003 and said the topic is relevant in today’s society.

“When we do nothing, students think it’s OK even if they didn’t intend to be offensive,” she said.

Sonja Crain, academic support coordinator in Student Support Services who has taught psychology courses at Simpson as an adjunct professor, said the hard-hitting lecture made her realize how prevalent microaggressions are even in her own classroom.

“It makes me wonder, ‘OK, where have I done it? How could I be recognizing it?’” Crain said. “I’ve never had any student say to me, ‘I feel uncomfortable with what you said or did.’ I haven’t had it brought to my attention, but I don’t want to make the assumption that I don’t do that. It really helps me be more conscious of that.”

After role-playing possible situations where a microaggression might take place, Souza presented a framework people can use to respond.

Microresistance, defined as incremental daily efforts to challenge white privilege as well as other kinds of privilege based on gender, sexuality, class and other indicators, help those who feel victimized cope with microaggressions.

This includes increasing personal and emotional strength, as well as social resources, by reminding oneself of their values, practicing self-care, which is not an equivalent to self-indulgence, finding and connecting with mentors and practicing gratitude.

“It’s not only really important to respond to microaggressions, but respond to the difficult dialogue,” Souza said. “And you can use this tool in a variety of different ways. You can use it with your housemate. You can use it with your partner tonight. You can use it if you’re frustrated with your dog just for practice.”

Souza offered the acronym OTFD, which she said could be used as a verb or a noun, where one can “open the front door.” It also stands for useful responses to a microaggression: observe, think, feel and desire.

For Crain, who has been teaching for 20 years, she plans to combat microaggressions to benefit all parties involved: “I’m going to get a little bit of a mantra going for myself, like ‘Here are some key words. Here are some key phrases to sort of kind of have in my arsenal so that I can handle it in an appropriate way that allows it to be a learning moment.’”

To mitigate or minimize the impacts of microaggressions, Souza offers these tips:

— Establish ground rules for interacting in class/meetings

— Don’t ask people to represent a perspective of an entire identity group

— Acknowledge and become informed about oppression of groups other than your own

— Be aware that your identity might impact others

— Be aware of your own biases

— Address microaggressions through microresistance