Tarver found his niche with Redmen football

February 20, 2003

Enjoying college was hardly a problem for Carlton Tarver.

The heavily recruited football star from Jacksonville, Fla. made a fairly quick and painless adjustment to college life. The fact that he was one of approximately 20 black students at Simpson in the fall of 1979 was practically inconsequential.

“If you’re playing football and doing well, you feel comfortable,” said Tarver. “I had an identity so I was accepted in a different way. It wasn’t a problem for me.”

Tarver came to Simpson at the end of a transitional period at Simpson in terms of its acceptance and enrollment of black students. There were more than 80 black students enrolled in 1976. That number had dwindled to just over 20 in 1982 when Tarver began his senior year.

Tarver arrived at Simpson at a time when a reversal in admissions policies was beginning to take its toll on black student enrollment.

In the late 1960s the college was determined to give disadvantaged students the opportunity to succeed at Simpson, according to Joe Walt, professor emeritus of history. The college began to recruit more black students, some of which were ill prepared for the rigors of college academics.

According to Walt, standards for admission were lowered in order to encourage disadvantaged students to enroll. For many black students at the time, they did not receive a proper college preparatory education. Their academic struggles became evident when classes began.

The Hawley Writing Laboratory was established in the fall of 1968 to offer “tutorial, person-to-person guidance” for incoming freshmen, in an attempt to get some of these black students on the same track as other students. This effort produced few results.

According to Walt, the drop in the enrollment of black students in the late 1970s and early 1980s was “the consequence of creating a single and higher standard for admission.”

Tarver, along with every other black student enrolled at the time, was just as qualified if not more so than every other student on campus.

When Tarver began receiving attention from the Simpson football coaching staff, he made a visit to Simpson and felt like every aspect of the college provided an opportunity for him to learn and be an active participant in the community. He felt Simpson would provide a different set of experiences than he would be exposed to at other schools that he was recruited by.

“Football didn’t overwhelm you,” Tarver said. “The school was interested in having athletes who were diverse and academically qualified. “

Tarver was further encouraged by the experiences of another black student, Gary Streaty, who graduated in 1981. Streaty was the student body president and a member of the football team.

“African Americans were doing things other than sports,” Tarver said. “I thought that if there was an African American who was doing all of this then it must be a good place.”

Tarver was also the only student during his four years at Simpson who held a Carver Grant. He majored in criminal justice and was a member of Student Senate. He spent two years as a staff writer for The Simpsonian.

His involvement with the football team provided Tarver with a college experience that was fairly different from most other black students at the time.

“I was in with the crowd,” he said. “I can imagine that for some students it was unbearable if you weren’t. With the football team, I had 100 people that I already knew.”

Tarver was a three-year starter as a defensive end. He became one of the main attractions for the Redmen and set the quarterback sack record. He was a team captain his senior year. His accomplishments got him inducted into the Simpson Hall of Fame in 1997.

His successful football career allowed him to identify with his teammates and the rest of the college community. That identity set him apart from many other black students on campus.

Tarver was invited to many parties and social events and was invited to rush a fraternity (an invitation he declined). But that was not true for some other black students.

“Some [black students] came socially to parties. But it didn’t really feel like you were a part of it,” Tarver said. “That might not be true but it was the perception. [Black students] weren’t totally a part of the social scene.”

While Tarver was an exception, most blacks were not invited to rush Greek fraternities or sororities. Black students saw this as having an effect on their chances of being elected to homecoming court.

Members of the Concerned Black Students organization had devised an answer to the concern – elect a black homecoming king and queen, a tradition that lasted for a number of years.

Tarver understood the thinking behind it, but still called the practice “irritating.”

While racial discrimination had lessened over the years, it still existed. The experiences of black students varied, and the administration began responding to the concerns of black students differently than they had in the 1960s and 70s when Garfield Jackson, class of 1969, said that an effective dialogue was created between black students and the administration.

“At one point, kids were walking around with black armbands,” Tarver said of one racial issue that surfaced. “It was perceived [by black students] that their issues weren’t as important.”

Tarver stepped back from most of those situations.

“I didn’t get involved because it didn’t do anything to me,” he said.

He blames part of the reaction of black students to their relationship with the college community.

“I found that kids that aren’t doing well are hypersensitive,” he said. “But in retrospect, [those issues] should have been a bigger deal. I’m happy with my experience, but there were things going on that weren’t as pure.”

Tarver notes one issue that he faced on the football team that made him wonder whether racist feelings motivated action by his teammates.

When the team’s post-season awards were handed out, Tarver thought that he would be awarded with player of the year honors. Many of his teammates thought he was a sure thing for the award.

“I was angry,” he said. “But looking at it now, you have to forget about it.”

Tarver graduated from Simpson in May of 1983 and joined the Des Moines Police Department. He then moved on to work with the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms in Omaha, Neb. for the next 10 years before being transferred to the bureau’s offices in Washington, D.C.

He is now employed with the state department as a personnel security manager, a job that has taken on new meaning since the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

“I do counter intelligence and manage the security of people traveling overseas,” Tarver said. “[Since Sept. 11] everything is tougher and stricter. I really scrutinize over everything now.”

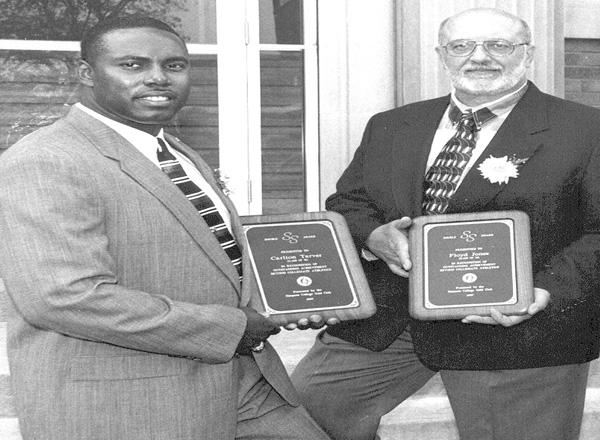

Tarver was also a captain in the Army Reserves from 1988 to 1999 and served in Saudi Arabia during Desert Storm. He was awarded Simpson’s “Double S Award” in 1997 for excellence in athletics at Simpson and achievement following graduation. He has helped recruit Simpson students, played a role in bringing former football coach Jim Williams to the program, sponsored interns and serves on the Criminal Justice Advisory Committee. He has kept Simpson close to his heart for the past 20 years.

“At Simpson I gained confidence,” Tarver said. “I learned to read and write to a higher degree.” That academic experience has taken him far in his post-graduate years.

And he gained an appreciation for interaction between races; an experience that he hopes Simpson strives to provide for present and future students.

“There is a respect that comes and barriers are broken,” he said. “You come to learn that minorities are the same.”