Iowa’s Indigenous communities faced with crisis of missing and murdered women

This article was written as a senior capstone project and was originally published to IowaWatch/Investigate Midwest on May 26, 2022

June 30, 2022

Rita Papakee’s family last saw her more than seven years ago.

At about 1 p.m. on Jan. 16, 2015, Papakee, 41, left work at the Meskwaki Bingo Casino and Hotel in Tama County, Iowa. She was reported missing by her family on Feb. 18, 2015, to the Meskwaki Nation Police Department after she did not pick up her last paycheck.

“Everybody is still wondering: Where is she, where is she?” Iris Roberts, Papakee’s mother, said.

Indigenous people are missing in Iowa, but disappearances span the nation.

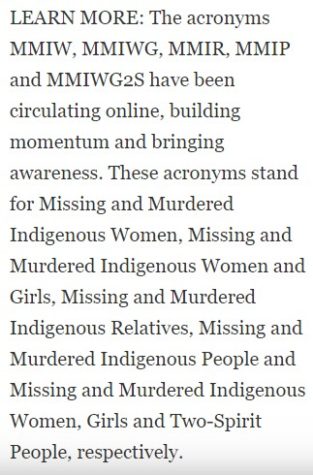

In 2021, 9,572 Native Americans were reported missing, according to information from the National Crime Information Center. Of those reported missing, 54.4% were women. Indigenous women and girls face murder rates ten times higher than the national average, according to research compiled in 2018 by the National Congress of American Indians.

The key findings of five months of interviews with tribal leaders, loved ones of missing relatives, and Iowa officials show:

- Because many Indigenous women are murdered off tribal land, who has authority to investigate cases can get murky.

- There is a lack of data on cases, such as not knowing the tribe a person belongs to.

- And often the effort to keep looking rests with family, friends or tribal members. Some of these missing person reports become cold cases, and Iowa lacks a dedicated cold case unit.

These missing Natives are a crisis, Charles Addington, an official in the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs, said in 2019.

The leaders of RISE, which stands for Resources for Indigenous Survivor Empowerment, said it’s a crisis that often is unheard of outside of these communities.

“I think a lot of people outside of the community aren’t even aware of what MMIW is,” said Nicole Lepley, director of RISE. “Just knowing what it is, looking it up and becoming more aware of the rate of violence against Indigenous peoples (is important).”

Lepley, who is not Indigenous, emphasized the need for more non-Natives to understand the issues facing Indigenous people, such as MMIW.

“Most often, perpetrators aren’t Indigenous. They aren’t from the community,” she said. “They come to tribal lands and commit crimes and aren’t prosecuted because of issues with whose jurisdiction it is. I think people who aren’t from the community don’t know those things.”

In 2021, 107 out of the 6,300 missing person reports in Iowa involved Native Americans, according to statistics from the Iowa Department of Public Safety. All are closed unless they are listed on the DPS website. Of those cases, 53 remain active.

Native Americans make up 0.5% of Iowa’s nearly 3.2 million residents, according to the most recent U.S. census, and 1.69% of the missing persons reports in Iowa in 2021 involved Native Americans. One issue: State data is not broken down by gender so it’s unclear how many are women.

Iowa woman’s disappearance

Just one disappearance can affect a community, especially one as close-knit as the 1,450-member Meskwaki Nation.

“It’s unsettling, and it seems like since that happened and we haven’t been able to find a fellow tribal member, it’s kind of like a dark cloud looming,” said tribal member and Meskwaki Police Department Commissioner Mark Bear.

Within the 8,100-acre Meskwaki Settlement, 4.5 miles west of Tama and Toledo, it’s difficult to go anywhere without seeing a missing person’s flyer asking to bring Papakee home. Flyers hang on the Tribal Center and in the police department.

Papakee is one of the first instances of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) experienced by the Meskwaki Nation, also known as the Sac and Fox Tribe of the Mississippi in Iowa, said Mylene Wanatee, Meskwaki Family Services director.

Papakee was a mother not only to her own children but to nieces and nephews. She loved baking and holidays and would plan activities for the children on Halloween and Easter, said Roberts, her mother.

“She was really kind-hearted,” Roberts said. “She would go out of her way to help people if she really thought they needed help.”

Papakee knew how to make people laugh, especially her mother, with whom she was close.

“Oh, my stomach would hurt. I’d say, ‘Quit now, Rita!’ and she would keep going, and we’d laugh some more,” Roberts said.

Papakee’s children have all struggled with their mother’s disappearance, Roberts said. The oldest is 27, another turned 19, a third is 17, and the youngest child 14. The family has asked for their names to not be published.

During the last seven years, officials have searched for Papakee. The Meskwaki police contacted the Iowa Air Patrol in March 2015 to scour the area from above while community members searched the ground in the following months.

Over time, police combed pig farms, wells, highways, structures, fields, dirt piles, areas of water and under bridges surrounding the settlement.

In May 2019, the Sahnish Scouts, an Indigenous North Dakotan non-profit organization specializing in search and recovery, looked along the settlement and in Tama County.

“We believe that just one tip could open this investigation wide open. We just do not know when that day will come,” Police Chief Jacob Molitor said in a 2019 press release.

The police declined to comment further.

The tribal council is offering a reward, now at $100,000 from tribal revenue, for information leading to the whereabouts of Papakee.

“We’re all doing our due diligence to make sure that nobody forgets and that we’re still looking for her. She knows that, too, wherever she is, we’re still looking for her,” Bear, the police commissioner, said. “It’s still looming in unexplainable ways. That’s just from a tribal member standpoint.”

43 years of seeking justice

Other Indigenous families in Iowa and the nation have been searching for answers to missing or murdered persons cases. They are often the ones who keep cases on people’s minds.

For 43 years, relatives have sought answers after Keara Lee Cosow, 3, was killed in a fire at the Hilltop Motel in Red Oak, Iowa, on July 12, 1979. No criminal charges have been filed in her death.

Keara’s mother is a member of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

Keara’s older sister, Jordan D’Mario, has dedicated herself to bringing awareness to Keara’s death and the inconsistencies in records. She uses social media networks such as Facebook.

The Facebook page, named after Keara, has over 200 likes and contains photos of Keara, her grave and newspaper reports from 1979. The case eventually made its way to private investigator Janet Franson, a semi-retired cold case and homicide detective from Florida. Franson tried to find an organization to take up Keara’s case but was unable to do so.

“I can still see that baby’s face,” Franson said.Franson and D’Mario said they believe the case should be reinvestigated.

“I just want Keara’s truth to come out,” D’Mario said. “I want justice for Keara.”

Challenges to investigating

Several acronyms are associated with the movement to end violence against Native women, children and two-spirit peoples, which is a unique gender identity in Indigenous cultures. MMIW and MMIR, for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives, are two common acronyms.

Despite recent awareness of MMIW, the crisis dates back to when Christopher Columbus first landed in the Bahamas in 1492. It was further perpetuated by the over-sexualization of Indigenous women in movies and television, according to the Great Plains Action Society, a non-profit collective of Indigenous peoples.

“I feel like this has always been something that has always happened since the first contact with settlers, so it was just something that we naturally became passionate about,” said Trisha Etringer, director of the MMIR initiative of the Great Plains Action Society.

Most murder cases are committed on Native land by non-Native people, and jurisdiction becomes cloudy among the state, federal and tribal law enforcement, especially when prosecuting non-Natives, according to a 2016 investigative report from the Urban Indian Health Institute, which is a division of the Seattle Indian Health Board.

This complex process can make it challenging to investigate. The institute’s report also highlighted a lack of an exact number for MMIW across the United States.

“The last statistics … were in 2016 and they’re inaccurate,” Manatee said. “They don’t even tell the whole story.”

In 2020, a federal task force was created by former President Donald Trump to address the MMIW crisis.

“We see there’s federal funding going to this task force and this is going to be what they’re going to work on, but we still don’t have accurate information,” said Lepley, RISE’s director.

Federal law requires federal, state and local law enforcement — but not tribal law enforcement agencies — to report missing people under age 21 but not those over 21, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Another Iowa cold case involves Sandra S. Vanderhoef, 42, a Native woman who was reported missing to the Webster County Sheriff’s Department on Sept. 22, 1986. Her last known location was at the Des Moines bus depot.

In the 36 years since, the department has lost all public records on Vanderhoef.

Vanderhoef’s disappearance has been classified by the Iowa Department of Public Safety Information Clearinghouse as “Endangered / Physical,” which includes a person of any age who is missing under circumstances indicating their physical safety is in danger.

Papakee and Vanderhoef’s cases are classified as cold cases, unsolved criminal investigations that remain open pending new evidence.

It is uncommon for a state not to have a cold case unit, said Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation (DCI) Associate Director Mitch Mortvedt. Iowa lawmakers introduced legislation to create one, but efforts stalled.

The current option is for local law enforcement or agents from the DCI to spend time between investigations and trials to follow up on other investigations. Most cold cases are investigated by the DCI, but the organization must be requested by a police chief, a sheriff or a court attorney in order to act.

Other priorities or more urgent cases can come up, and then “the cold case gets put away again,” Mortvedt said.

In the meantime, activist groups and tribal resources tackle the cases.

Activists seek to make a difference

Etringer, a member of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska and with the Great Plains Action Society, leads a campaign to aid Indigenous families who have had missing or murdered relatives. The pull to the movement was personal.

“My auntie went missing in the ’80s,” Etringer said. “We found her, thankfully. Sometimes it doesn’t end up like that. I’m very thankful that we at least got to have some kind of, you know, not really closure, but we found her, and we know what happened.”

The group began after losing members during a protest against the Keystone XL Pipeline in Lincoln, Neb.

“Literally right after that, we had about two girls that went missing, and they were murdered, Etringer said. “Shortly after that, another girl went missing. Those lines of events really pushed it for us to get involved.”

The Great Plains Action Society provides resources such as mutual aid. This can be used for anything from car seats for parents in need to funeral expenses.

MMIW cases can also happen outside of Indian Country. This leads to a need for more non-tribal police and governmental bodies to understand the crisis, officials said. According to the Urban Indian Health Institute, 71% of all Native Americans live off federally defined tribal lands.

Within the Meskwaki Nation, RISE provides resources and emergency services to clients who have been displaced or need help as a direct result of domestic violence or sexual assault. RISE also provides help to families affected by MMIW for any Indigenous person in Iowa. The organization can only do so much.

“I honestly want the state to have to focus more on MMIW, not only that but other Indigenous issues that we run into,” said Wanatee, the Meskwaki Family Services director. “We can only do so much.”

EVENT: The Meskwaki Nation Police Department and RISE are working to keep Rita Papakee’s case and memory alive through events such as memorial walks.

The next walk will be June 1 for Papakee’s 49th birthday.

“We’re planning to walk from a certain destination just to bring awareness, and we have like facts of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People along a trail so that people can kind of understand it more because when you see the numbers, it’s more realistic,” Alanna Holiday, of RISE, said.

The walk/run will be held at 5:30 pm; the location is to be determined.

This article was written as a senior capstone project and was originally published to IowaWatch/Investigate Midwest on May 26, 2022