Undocumented in Iowa: A student’s pursuit of happiness

April 4, 2017

INDIANOLA, Iowa — When she was 8, Drake University senior Kenia Calderon attended her first college class in El Salvador with her mom and discovered the thing she wanted most in life: a college degree.

Now pursuing her degree in business and entrepreneurship, her goal is to run for public office one day, advocating for other undocumented immigrants like herself.

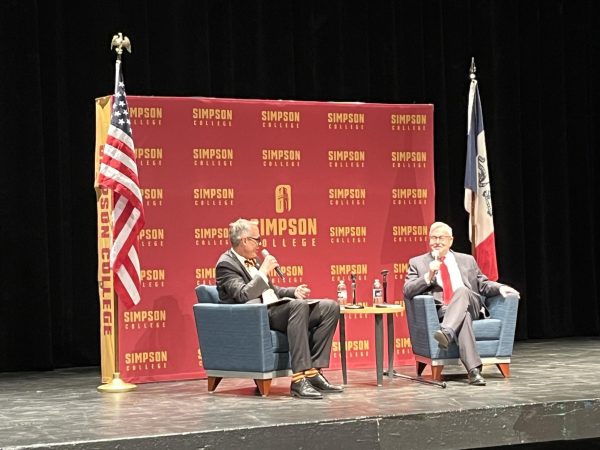

Calderon spoke at Simpson College on March 29 about her journey to Iowa, her experience in the United States and dispelling common misconceptions about undocumented immigrants.

Many migrant workers in Iowa are undocumented, seeking work on farms like the ones taken from them in Central America. Calderon reminded the audience, however, that living in the United States unauthorized is not a crime. Furthermore, crossing the border is a simple misdemeanor, just like running a red light.

Though the media often portray undocumented immigrants as criminals, people forget that immigrants usually come to another country seeking a better life, one from economic collapse, drug trade and crime.

“El Salvador is the No. 1 murder capital of the world and we’re not even at war,” Calderon said.

She said many children like her realize the danger around them at a young age.

“Many children in Central America don’t have a childhood because they know how dangerous it is for them to exist,” she said.

When Calderon and her siblings started getting older, her parents realized their chances for a good life were slim if they stayed. So they began the journey from El Salvador to Iowa. And many in Central America today are choosing to do the same.

“I can’t blame somebody for wanting to survive,” Calderon said. “I don’t think wanting to live is a crime.”

One stop in Guatemala, stalling in Mexico for a month and crossing the border on foot for three days, Calderon and her family made it to Iowa. She knew her life would never be like everyone else’s here, and it became apparent to her quickly.

“I went from seeing my dad work in an office to cleaning toilets at McDonald’s. That’s when reality set in for me that he had given up his career for us and now he was being treated as if he didn’t have any value,” she said.

Despite living in Iowa since she was 11, Calderon still worries about her future and how long she has left here. Simple tasks like driving to school become risky. If she is pulled over for something as small as a broke taillight, she could be subject to deportation.

“Even going to church now, we have to be careful. We have to take different roads and change the way we get to places,” she said. “Recently, whenever someone knocks on our door is terrifying.”

As much as Calderon worries for herself, she worries far more about her family. She thinks of her sister, soon to graduate high school and attend college, following in her footsteps. If Calderon’s family is ever forced to return to El Salvador, her hope is that they all at least have a college degree.

Still, she fears for her parents who gave up so much in hopes that their children could have more.

“Every day there’s that fear that I don’t know if my parents are going to come back from working,” she said.

Being vocal about her experiences, talking at colleges, participating in documentaries, all of these things draw attention to Calderon, putting her at a higher risk of being found and deported.

But she said there’s no way she can go back now, even if she wanted to.

“I choose not to be afraid,” she said. “Because I’d rather go for doing something that means something to me than go feeling bad for something that I know does not.”